How DACA Helps Both the U.S. and Everyone Living In It

November 10, 2017

Imagine growing up in America, going to school in America, speaking English, learning American history, and living the life of any average, standard American child. Then as you grow up, you are unable to apply for a driver’s license or apply to college, all because you do not have a social security number, because you are an undocumented immigrant.

For many hundreds of thousands of people, that is not hard to imagine. They lived it. For many of them it shifts their view on the country they call home. For many it is a revelation that they did not foresee.

Since the early 2000’s, there has been bipartisan legislation floating through the halls of the U.S. Capitol building, to protect undocumented immigrants who were brought into the United States as children. Even though polling by the National Religion Research Institute shows that current public opinion agrees that childhood arrivals should be granted amnesty and legal residency status, none of these attempts at a legislative solution have ever been voted into law.

After several attempts at passing varied versions of the Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors Act (DREAM Act) with no passage of any such legislation, President Obama took matters into his own hands. On June 15, 2012 Obama announced an executive action creating the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. The DACA program allowed undocumented immigrants, who were brought to the U.S. as children, to apply for deferred action from deportation, as well as a work permit. In addition to these benefits, they paid taxes, and were able to attend higher education institutions.

Not just anyone was eligible for the DACA program. There were a series of criteria that each applicant had to fulfill in order to receive the benefits that accompanied the program. The criteria laid out by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service has seven key points.Firstly, you had to be “under the age of 31 as of June 15, 2012,” have come “to the United States before reaching your 16th birthday,” and “have continuously resided in the United States since June 15, 2007, up to the present time [June 15, 2012].” Applicants must have also been “physically present in the United States on June 15, 2012, and at the time of making your request for consideration of deferred action with USCIS,” and have been undocumented as of June 15, 2012.

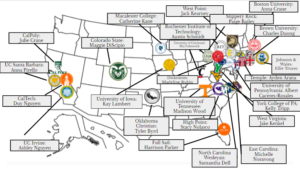

The requirements were more than just the who, the where, and the when of each applicant’s individual situation. All applicants had to have been enrolled in high school, have graduated high school, or have received a general education development certificate (GED). If an applicant had left school to enroll in the military or Coast Guard, they were also eligible if they had been honorably discharged. In addition to the educational requirements, all applicants had to show, as the DREAM Act of 2010 expressed it, “good moral character.” The exact articulation of the executive action read, “[The applicants may not] have not been convicted of a felony, significant misdemeanor, or three or more other misdemeanors, and do not otherwise pose a threat to national security or public safety.”According to a study done by the Pew Research Center, a non-political think tank based in D.C., upwards of 790,000 undocumented DREAMers have been shielded from deportation and been made eligible to work through the DACA program. These benefits have allowed DREAMers to seek out opportunities not previously available to them, economically, socially, as well as educationally. In a study conducted for the Center for American Progress in August of this year, Tom Wong, a professor and researcher from the University of California-San Diego found that the wages of undocumented immigrants increased by 80 percent once they received DACA protections. More than half of the recipients also purchased a new car, and almost a fifth purchased their own house. More than half of the DREAMers reported being able to pursue jobs that were not previously available, as well as getting paid higher wages.

In 2014, President Obama sought to expand Deferred Actionfor Childhood Arrivals, as well as enact Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA). Both of these programs would vastly increase the number of undocumented immigrants eligible for deferred action and other similar benefits. DAPA sought to protect the undocumented immigrants in the United States who had children who were either native-born American citizens, or naturalized American citizens. These two initiatives were accomplished through executive action, following a continued legislative stalemate.

Before the implementation of DAPA and the DACA expansion, the office of the Texas attorney general filed an injunction in federal court, claiming that both of the programs were unconstitutional. Twenty-five other state attorneys general joined the case. United States vs. Texas was eventually appealed to the Supreme Court by the Obama Administration. The Supreme Court was split, with no decision being made after the justices ruled 4-4. With no Supreme Court ruling, the previous, lower courts’ ruling were upheld, and an injunction was issued, stopping the expansion.

The states that filed the injunction believed that the president did not have the power to grant legal status to undocumented immigrants, and that by doing so, Obama had violated the Constitution, and overstepped his executive powers. They argued that he had effectively created new legislation, an action that only the U.S. Congress could take.

The Obama Administration argued that they had not granted legal status, but merely legal presence. They stress the importance in the distinction. They called their actions an exercise of an executive authority called prosecutorial discretion. Prosecutorial discretion is the prerogative of an agency or branch of the government to make decisions on what kinds of cases they might decide to prosecute. For example, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) may decide to not seek prosecutions against small-time, non-violent marijuana users, and that would be their use of prosecutorial discretion. The advantages of not seeking to prosecute all cases is that they are able to allocate more time, resources, and personnel to scenarios they consider more dangerous, pressing, or merely higher priority. So to use the previous example, the DEA may allocate those newly available resources to the investigation and prosecution of international drug trafficking rings, a higher priority situation.

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals has had an unboundedly positive impact on undocumented immigrants, the overwhelming majority of whom have known no other home than the United States. According to Wong’s study, 72% of the top 5% of Fortune 500 companies employ DACA applicants, meaning that their purchases, contributions, and tax money has all fed into making the United States a better place.